As part of my workshops on effective communication, especially around introducing innovative new process approaches such as Lean and Agile, I’ve found examples that demonstrate how people can act with “skilled incompetence” and “skilled unawareness”.

One exercise I run is to help people look at how effectively they communicate feedback on difficult topics. The scenario (based on Argyris’ XY case study) is that a manager, Y, has given some feedback to a poorly performing team member X. I show the participants a list of comments that Y (the manager) has said to X (team member) and ask them to pretend that Y has come to them as a coach and asked:

Can you review the feedback I gave to X? I’m interested in learning how to improve – how effective was I?

At the recent London Software Practice Advancement (SPA2011) conference, I ran this workshop and one of the workshop participants said they’d give Y the following feedback:

Y, your feedback to X was ineffective because you failed to focus on things that X was doing well, and you also didn’t illustrate your feedback with an example of what X specifically did

I think the participant’s statement illustrated that we tend to store theories of effective behaviour in our heads. In this case, the participant’s feedback contains a micro-theory that:

Feedback is effective when it:

1) focuses on behaviours that are done well and

2) illustrates the feedback by using a specific example of the behaviours.

The participant confirmed that this was their view.

I was curious then to apply the participant’s ideas about effective feedback to the feedback they gave Y. I asked:

Let’s use your own theory of effectiveness to analyse the feedback you gave Y. I don’t think your feedback was about something that Y was doing well and I don’t think you gave an example of what Y specifically did. Do you see it that way or see it differently?

The participant agreed that the feedback they provided was not consistent with their own beliefs about effective feedback, and they also confirmed that they were able to see the inconsistency once it had been pointed out, but they were unaware that what they said was inconsistent when they originally produced the feedback.

In effect the workshop participant was telling Y, “do as I say, but not as I do” without admitting this directly. It’s likely that the recipient of the feedback, in this case Y, will experience it as inconsistent and puzzling.

This small example illustrates several points of Argyris’ concepts of skilled incompetence and skilled unawareness. Firstly, the fact that participant’s comment was incompetent in the sense that it did not meet the participant’s own beliefs about effective feedback. Secondly, the feedback was skilful in the sense it was automatically produced without the participant being aware of the inconsistency. Argyris refers to the lack of awareness of our own skilled incompetence as skilled unawareness.

Although it’s common for most of us to admit we can sometimes act in a hypocritical way, most of us are not aware that we are doing so when we are producing the action.

There are many benefits from accepting and finding ways to overcome our tendency to act with skilled incompetence and skilled unawareness. Adopting the mindset and behaviours of the mutual learning model (based on Argyris & Schön’s Model II) involves accepting we can act like this and choosing to act in ways that invite others to help us realise it in order to be more productive. I’ll write more about this in future.

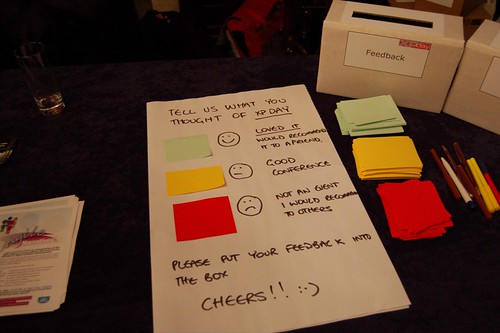

Photo credit: Adwale Oshineye

Leave a Reply